I've always wanted to make a game similar to Ogame, TribalWars, or Hattrick. For whatever reason, I've always loved the idea, even though I've never really had enough spare time to invest in these types of games, since most are long-term games, especially Hattrick, where achieving goals can take years.

A few weeks ago, I considered creating one, and after some time programming, I realized that what I really needed first was a design.

Of course, this is just my take and it may not be 100% accurate or there might be things you'd do differently. But as a starting point and an exploration, I think it’s quite interesting.

Table of Contents

1 - What is a browser game?

A browser game, as the name suggests, is a type of game you access through your browser, where you act as a manager or administrator of an environment or system. These games are all about resource management, maybe you’re the owner of a team, managing the stadium, hiring players and staff, etc. (like in Hattrick), or the leader/owner of a planet tasked with managing resources, dealing with attacks, and so on (as in Ogame).

The fun comes from competing against other people to see who is the best (PVP), with a focus on long-term strategy. In Hattrick, for instance, where you’re a soccer coach, moving up just a couple of divisions might take you years (or even longer).

In short, it could be described as playing Excel. * This is a meme for all Football Manager fans.

Nowadays, unless you're doing this to learn, creating this type of game is almost a suicide mission, because the mobile games market has completely taken over. Ultimately, your competition is Clash of Clans and similar games, which is impossible to compete with as a solo developer due to all the aggressive techniques they use. They seem more like slot machines than games, but that’s another story.

1.1 - Real-time browser games

When I was a teenager, browser games became a bit popular. In fact, there was one that stood out, I’m not talking about Habbo (I never played it and don’t know if it ran in a browser).

I’m talking about Brute, like Hattrick or Ogame, it was played in the browser, but with one key difference: the PVP was real-time. That’s what we’d now do with Websockets, or SignalR if you’re using .NET.

So if you want something real-time in your game, as you can see, it’s not that hard to add.

2 - Game design

2.1 - Choosing the game style

My first thought was a pirate game, where you’d have boats with crews that go out to sea to fight, and a world full of islands, basically like One Piece.

But this brings several complications, most notably the boats, what do you do with them? I’d want it to be realistic, which means you can’t attack with 100 boats and have all of them land simultaneously; that’s not how it works. Each island should have a percentage of land where you can land and continue from there.

As you can see, even with the first idea, implementation gets complicated, details that might seem small, but are really important and consume all your time.

So at that point, I put aside the pirates idea and decided to do something simpler: battles on foot. I could’ve drawn inspiration from my favorite series for the design, but my idea was just to create a sketch of the concept, something tangible. I went with what you’re probably all thinking: Age of Empires. Soldiers, archers, knights, and after the sketch, siege weapons and cars that shoot 👀.

The idea is to capture this in a browser-based, non-real-time game.

If you research, you’ll find that this already exists, it’s called TribalWars and it came out in 2003 (there’s a sequel too), so we won’t be launching this to production, but it’ll help us learn and keep our brain working for a while.

Once you have the theme, it doesn’t matter if it’s the Middle Ages (TribalWars), an ancient Greece simulation (Ikariam), or an alternate version of Star Wars (Ogame), they’re more or less the same. You have your city/planet and attack others, and the cost of attacking, both in resources and time, depends on the distance to that location. At this point, you’re probably already imagining your own scenarios, that's how the overall mechanic works.

2.2 - Resources and progression

One of the most important parts of any game is to keep people interested in it, I don’t mean addicted, since that would require manipulative techniques I don’t agree with, but at least interested in logging in regularly.

You need great progression. You don’t want players reaching max level in a day, nor do you want it to be impossible, progress should be gradual.

This is where resources come into play, because they’re the simplest way to regulate progression.

All these kinds of games have a resource system, either basic resources used to construct buildings, or coins/tokens linked to real money.

In this section, we're talking about basic resources.

In short, you need resources both to create troops and upgrade buildings.

For example, let’s say the resources are food, wood, iron, and stone. Each of these comes from a specific building.

Wood is produced at a sawmill, stone comes from a quarry, iron from a mine, and food from a farm.

If we wanted to be really realistic, we could set limits, how much iron can be mined, how many trees in a forest, or minimum/maximum number of farms, but extreme realism isn’t just technically hard, it might drive away casual players (and hardcore ones don’t really care). So, it’s better to have a building that generates X resources per hour, plus requirements to upgrade it so you can get more per hour.

On top of this, timing is crucial: the early levels are fast to give users a sense of progress, while the later ones are much slower to show it’s a tough task and that decisions must be considered carefully before upgrading.

The same applies to troops, they cost both basic resources and time to make.

2.3 - Monetization in browser games

For better or worse, we have to monetize our app, servers aren’t cheap. These games allow for administrative benefits when paying for premium, but aren’t pay-to-win.

This means that when you pay, buildings and troops don’t finish faster, cost less, nor do they become stronger or yield extra resources.

NOTE: Ogame does do this 🤦

Then why would anyone pay?

Remember when we said progression is slow? What if a building takes 10 hours to build and it finishes at 3 AM? If you want to upgrade another, you’d either lose precious construction time while you sleep or pay for premium, which lets you queue another upgrade automatically.

The same applies at night, you can schedule attacks to launch during the night without being present yourself. As you can see, these are administrative perks that don’t accelerate progression, so it isn’t unfair to other players.

How much you include in the premium tier is up to you, but it should only be enough that paying is worthwhile without making non-payers feel they can't play.

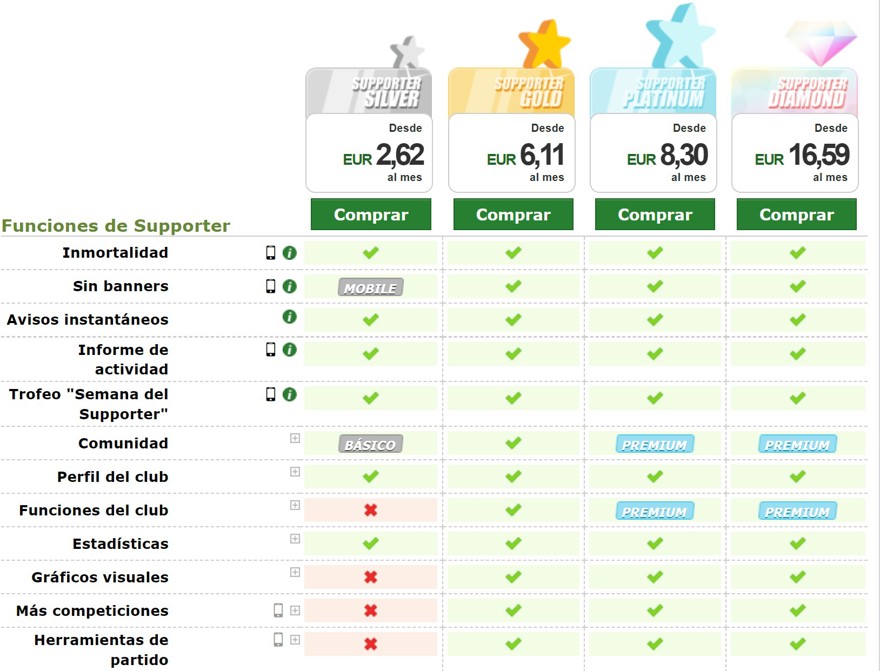

In Hattrick’s case (a football manager simulator), there are 4 different premium tiers -https://www.netmentor.es/entrada/suscripciones-stripe-, with the two most expensive allowing users to manage a second team (that’s actually the only difference between gold and platinum).

NOTE: Hattrick is built using .NET, at least the interface is ASP.NET Framework -https://www.netmentor.es/entrada/explicacion-versiones-dotnet-.

2.4 - The game engine

The game engine is not like a “normal” game, I’m not talking about Unity, Godot, or your own engine. In these games, the engine is actually your server, running all the infrastructure.

I’m referring to the combat engine (as in TribalWars or your own combat game) or the match engine (in Hattrick).

It’s very important to keep the engine as “realistic” and neutral as possible so everything is fair for everyone.

Because, as happened in the first generation of Pokémon with psychic types (which had no counters and everyone played Mewtwo), your game might be unbalanced. The best was mine with psychic, recover, ice beam, and thunderbolt.

Ideally, you should run a lot of simulations to ensure there isn’t a composition that breaks game balance.

2.4.1 - Game graphics engine

While the most important thing is troop balance, graphics also matter. In our case, we don’t need much, just a village graphic as a base, and buildings whose appearance changes with their level. That’s if you want something graphical; if you want a true Excel simulator, just displaying the data is enough (like Ogame does/did).

3 - Implementing the game engine

In our case, the key is combat, and while I’m not going to reveal the Holy Grail, I’ve given it a lot of thought and I have a version I might, one day, put on GitHub.

When we talk about battles, we’re talking about several things; battalions and combat are the basics. So, how should we approach combat?

We could do something similar to Risk: attack with 10, defend with 12, and roll dice until one side runs out of troops.

Implementing that is the simplest option, probably assigning a point value for soldiers, 0.8 for archers, 1.3 for cavalry, etc., and repeat as needed.

However, I'm a huge fan of RTS (like Age of Empires) and turn-based games, so here’s what I thought, and I’ll show the mental process I went through.

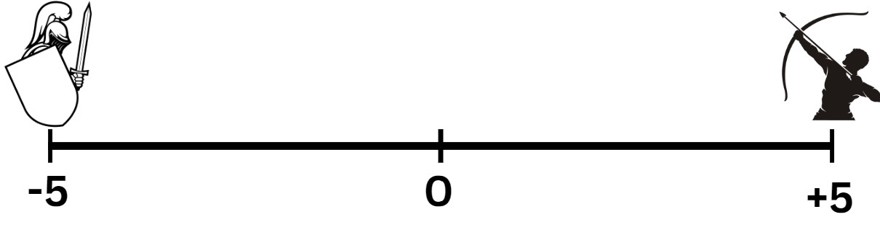

First, I imagined a 1 vs 1 fight, since it’s the simplest case.

In my example, a soldier vs an archer.

Obviously, the archer can attack at range and the soldier can’t, so you can’t just put them face-to-face and start; that’s not realistic.

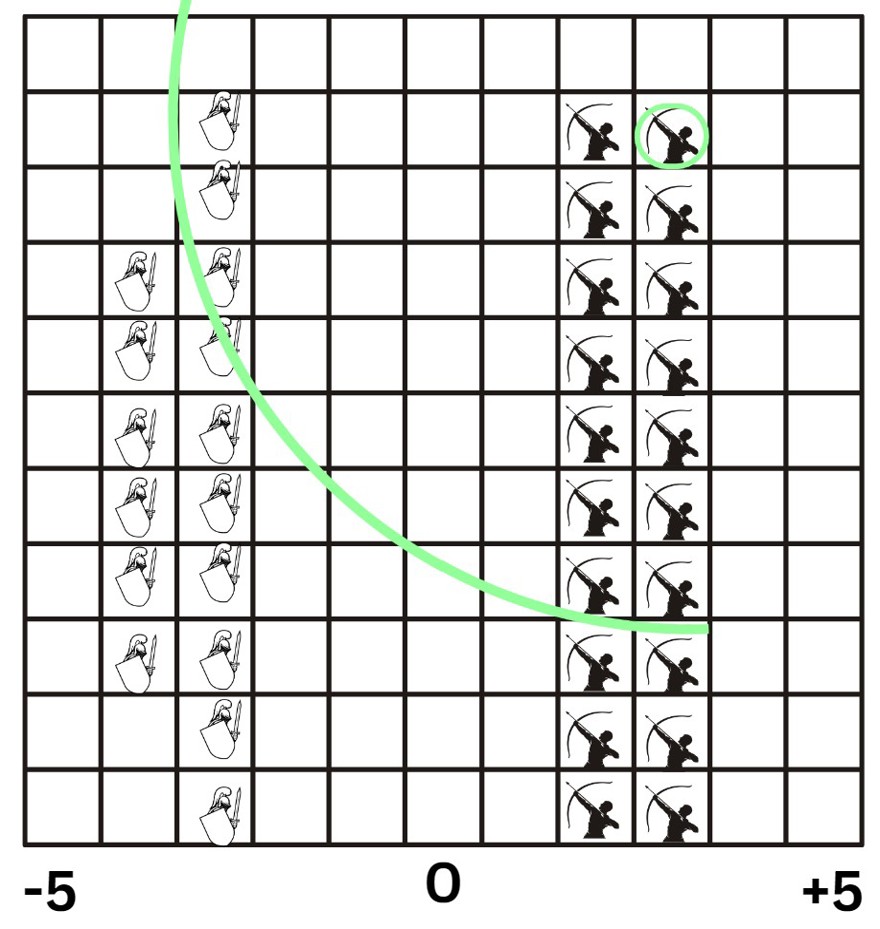

What I came up with: a map where the troops are separated by 10 units (these units represent distance, whether movement speed or range). For example, I set the archer’s range at 7.

This means for the archer to hit the soldier, either the archer or the soldier has to move closer.

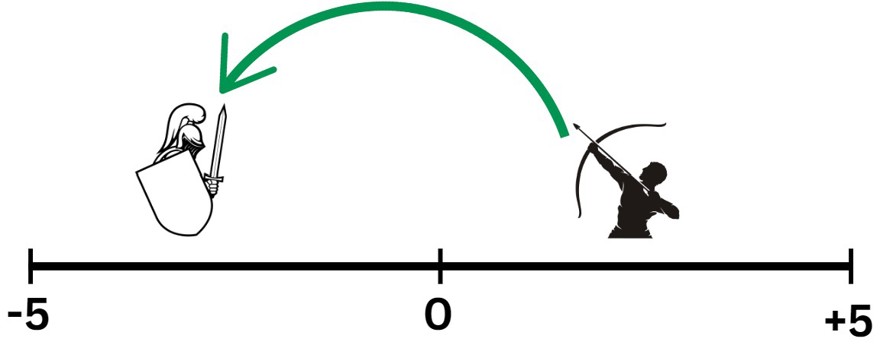

And to allow movement, we need to know how many times per game the troops can move. Here I introduced a turn system: each battle gets a random number of turns between 8 and 12. Why those numbers? I don’t know, it’s just the first version, so 8-12 is as valid as 14-25.

Another key element in turn-based games is that a user moves everything (either one or all troops) in succession, without enemy interruption. For me, that’s unfair. In my opinion, both should move, then attack, so that’s how I handle it, turns are simultaneous.

So, first turn: 10 units apart.

Since the soldier can only attack at 1 unit, he must move, and likewise, since the archer can't reach, he also has to move.

This means both move, which is VERY important. Why? If the soldier moves 3, the archer wouldn’t need to move and would be 7 units away, BUT since both move, the archer is now 5 units away, meaning the soldier can reach to attack sooner. I hope that’s clear.

And the same goes for attacking, if both attack, attacks resolve simultaneously and casualties are calculated at the end of the turn.

Note: Right now, troops attack once per turn.

This would be the situation at the end of the first turn:

Note: I checked the code, archer moves 3, soldier moves 2.

Of course, archers have a small miss chance, and soldiers’ damage considers the arrow’s power and armor, etc.

On the next turn, the soldier will move and the archer will just attack. This cycle repeats until either one dies or the turns run out.

3.1 - Implementing battalions

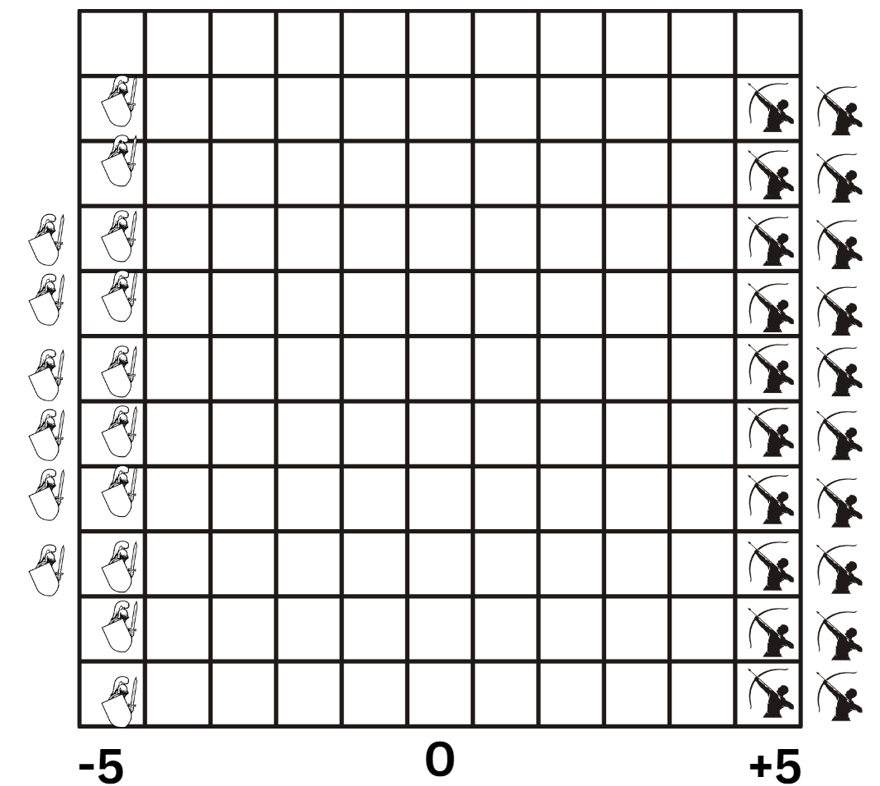

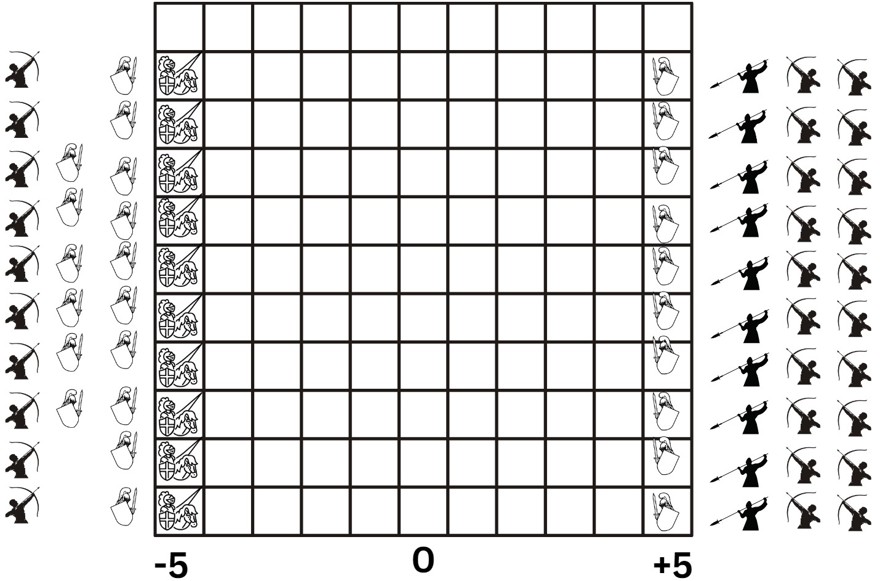

But, of course, nobody attacks or defends with just one troop. Ideally, we’ll have battalions. For now, let's keep a single unit in each battalion; the battle might look like this:

This is a very basic example, but it illustrates a number of problems we’ll face.

The first is the size of the battlefield. 10 units isn’t enough. We need a battlefield width, ideally different for every village, and each flank should have its own, forcing attackers to scout before attacking.

One thing you notice: not all archers can hit the same places at 7 units range. For instance, the top right archer can attack these positions after the first turn:

Meaning, to hit the ones below, the archer has to move on the board.

A possible solution is to treat all troops as one and handle logic at that level, and that would work, but it’s a bit bland, to be honest.

We’d need to research whether it’s worth investing in individual or group interactions.

But let's continue. Our battalions aren’t just soldiers and archers, they also have knights or spearmen (ideal against cavalry). And if we use the movie 300 as a base, spearmen have a range of 2 units.

I think it’s clear now: we need a much bigger battle map, perhaps 30 units of distance or more depending on the unit limit, and definitely taller as well.

Movement rules also get more complex: troops shouldn’t occupy the same square or pass through others, requiring pathfinding algorithms.

3.2 - Implementing formations

Placing units around the map lets you choose formations, the one in the previous image could be considered a line formation or default formation.

But what if you want a bigger attack from the flanks and less in the center? Maybe you know your opponent uses a defensive setup and want to break through specific spots.

Or if your opponent only defends with artillery, having spread out troops is important to avoid multi-hit attacks. Yes, this is common in Age of Empires. And yes, I’ve played a lot.

For me, formation is a basic feature in strategy games and essential for an engine.

Of course, the downside is you’d have to pick the formation before the fight, but that’s fine as long as you limit the number of available troops.

With formations come orders, maybe you have only one flank attack while the other stays back to attack later after soldiers move.

All these little variables make programming an engine for this kind of game really challenging, but also super fun.

4 - Architecture of a browser game

Finally, let’s talk about the architecture behind a browser game. We could put everything in a monolith and, when attacks happen, just execute a background task to get the result. For an MVP, that's fine.

But what’s the fun of this post if we just say a monolith is enough? Let’s make a distributed architecture for what would be ideal.

The frontend is pretty basic, simple views, whether you use SPA or not. At the end of the day, you just need to display simple info on the screen, maybe use pooling whenever a timer (for attacks or resource collection) finishes to refresh that section.

The tricky part is the backend.

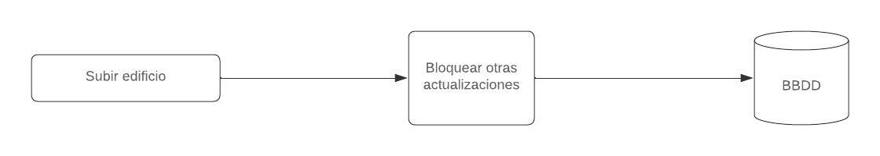

For example, what happens when you upgrade a building? The interface will show a timer indicating upgrade time, but what about the backend?

First you need to lock the database so no other updates can happen.

But you also need to ensure that when the timer reaches 0, the building upgrades and the interface unlocks.

But you also need to ensure that when the timer reaches 0, the building upgrades and the interface unlocks.

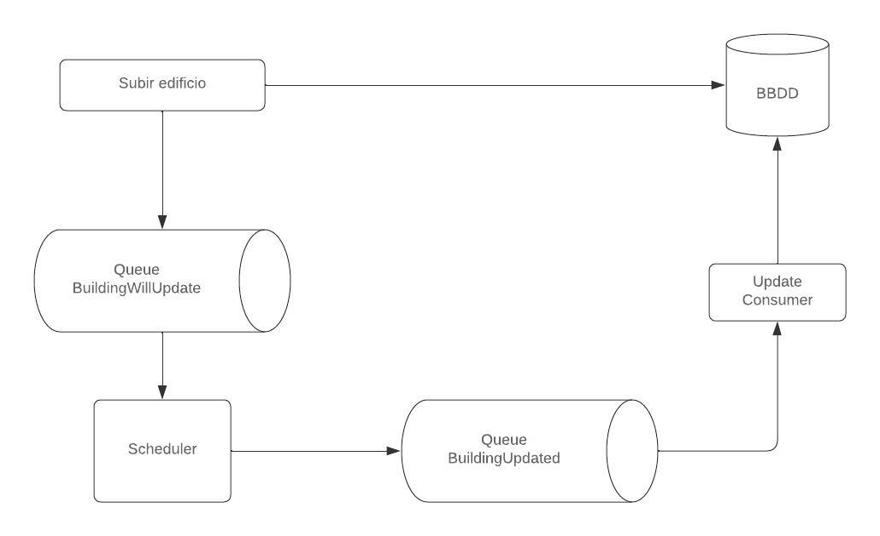

For this, you need a distributed job scheduler, or a system of background tasks that fires events when an action should happen.

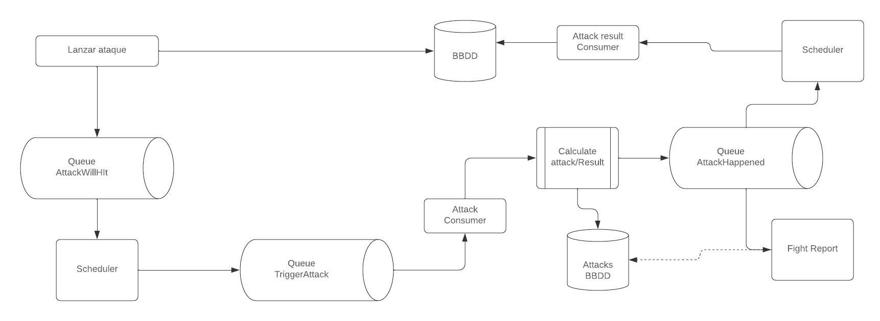

For example, back to the previous case: when a user clicks the upgrade button, we generate an event (Pub/Sub), which is read by our scheduler system.

When it’s time, the scheduler triggers another event with the info needed to upgrade the building, which is handled by a consumer with database access:

The same process happens with attacks, we generate an event for the attack time. While the troops are attacking, the available troop count in the city is locked, so you can’t attack other targets.

So, when they arrive, the scheduler generates an event, and the consumer calculates the fight, the report, and “returns” the remaining troops that then need to be updated when they get back to base, requiring yet another system and another scheduler.

All these event interactions take milliseconds, and we do things this way for several reasons. First, it guarantees that events fire; if not, because a system is down, we can always replay them exactly as they were at that moment.

Separation of responsibilities is important, as is scalability. Early in a game’s lifecycle, there will be more building upgrades than attacks, but over time, attacks outnumber upgrades.

Note: We've left out use cases like canceling an upgrade or attack, but I think you get the idea.

If you have questions about distributed systems, don’t forget that this website has the best free course in Spanish on them.

Here’s the Distributed Systems course (free).

Finally, I want to mention something that just occurred to me: knowing what I know, I could always keep the API open (auth required) so anyone could build their own frontend if they wanted. Don’t like how I made the website? No worries, make your own ;)

If you enjoy the content, don’t forget to leave a comment below, maybe we can make a series building this game!