As happens every year around this time, let’s take a look at the list of new features brought by the latest version of C#, in this case, the new features of C# 12. There are still a couple of weeks left before the official "release" of the version, but all updates have already been announced, so let's go over them.

Table of Contents

1 - Primary constructors for class and struct

Let's start with primary constructors. You might be wondering, what is a primary constructor? Well, if you’ve worked with records in C#, you already know that you can specify the “parameters” directly in the record’s definition, instead of creating the properties/fields separately.

That’s basically what a primary constructor is. Until now, it was only possible for records, but from now onward, it will be possible for classes as well as structs:

//Normal:

public class User

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

}

//Primary constructors:

public class User(string Name, string Email);This change might seem trivial, but I always use it when working with records, so I hope to do the same with classes and structs. Not to mention the amount of code we'll save by using this.

By the way, this means that from now on, your class won’t have a default “empty” constructor. Also, having primary constructors does not block us from creating additional constructors or other logic within the class itself.

2 - Default values in lambda expressions

Starting now, we’ll have the ability to set default values when we define a lambda. Imagine you have a delegate that receives a value and concatenates it into a string:

var buildString = (string s) => $"El valor es {s}";

string result = buildString("test");Now, you can set a default value in that lambda:

var buildString = (string s = "test") => $"El valor es {s}";

string result = buildString();

It may seem minor, or at first you might think it’s not particularly important, but for me, it adds consistency to the language. If you can specify default values in a regular method, why not in a lambda?

3 - Type aliases

For a long time, we’ve been able to use an alias for a class when there’s another in a different namespace with the same name. You’ve probably encountered code like this:

using MyUser= namespace.dentro.de.mi.poryecto.User;This is what’s called an alias. Starting with C# 12, we can define types in a similar way. To explain: we declare a name, like we do now, and just specify a name and define the properties it will have:

using CustomUser = (string Nombre, string Apellido);

using UserIds = int[];As you can see, in this case, it acts like a tuple, and personally, that’s the only use case I find logical.

Sometimes we’ve needed to create a class just to pass 3 or 4 arguments to a method, but the method’s signature gets too big or for another similar reason. In the end, you probably use a tuple a bunch of times. With this, that problem ends, since you only need to define it once.

Personally, I think that with primary constructors, a private class within the class itself is more useful than this, but well… I just hope this functionality doesn’t end up overused, as in my opinion, it could make things harder to maintain.

4 - Collection expressions

For several versions now, C# has been making improvements around declaring collections and expressions. In C# 11 we saw list patterns, which are mainly used with the spread operator (the two periods ..).

Among other changes, you can now merge multiple arrays using that operator:

int[] row0 = [1, 2, 3];

int[] row1 = [4, 5, 6];

int[] row2 = [7, 8, 9];

int[] single = [..row0, ..row1, ..row2];

foreach (var element in single)

{

Console.Write($"{element}, ");

}

// Output:

// 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, Since there are many features related to collections, here's the original Microsoft blog post.

5 - InlineArray attribute in C# 12

Let’s pause for inline arrays. This feature, I wasn’t even sure if I should include it here because I’m not sure who’s going to use it.

Inline arrays is a C# attribute that lets us define a sequence of primitives. As you’d expect from an array, you need to know the size, but not when instantiating it, rather, it’s defined at compile time, because that’s when the array’s size is set:

[InlineArray(10)]

public struct TestArray

{

private int _element;

}

//Usage

TestArray array = new TestArray();

// Iterate just like a normal array

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

array[i] = i;

}

foreach (var i in array)

{

Console.WriteLine(i);

}Because its content must be primitives, we can create the InlineArray as a struct, and thanks to this it will be located on the stack, not the heap, making it more efficient.

Now that it’s explained, like I said before, who’s going to use this? Maybe game developers?

6 - Interceptors in C# 12

C# 12 introduces interceptors, which feels a little like deja vu since interceptors already exist, we’ve already seen them in this blog with Entity Framework, and if I recall correctly, they’re also in .NET Framework. Though honestly, I never personally used them.

But these C# 12 interceptors are different; only the name is the same. Once again, in my opinion, Microsoft didn’t quite nail the naming.

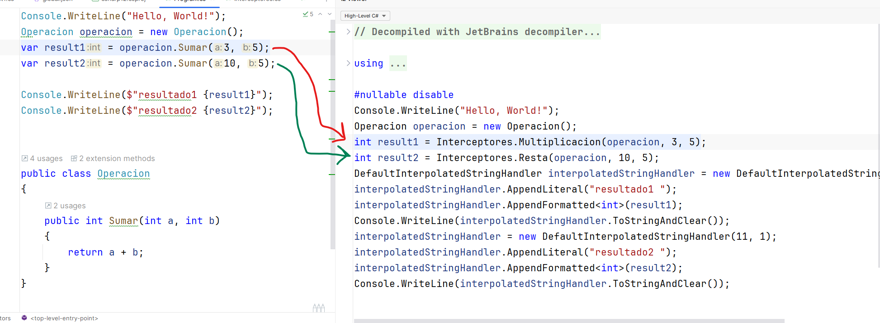

So, what’s interesting: an interceptor is simply a method that replaces another method by calling itself; this means the code we write will replace the existing code.

And this substitution happens during compilation, not at runtime, thank goodness, because if it were at runtime, well, hacks everywhere.

Here’s a simple example: first, you need to enable the feature in your project

<InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces>$(InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces);Interceptors</InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces>This means they are still in preview mode, not officially released and subject to change. Now you need a class, which is an attribute where you create your InterceptsLocationAttribute:

namespace System.Runtime.CompilerServices

{

[AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.Method, AllowMultiple = true)]

sealed class InterceptsLocationAttribute : Attribute

{

public InterceptsLocationAttribute(string filePath, int line, int character)

{

}

}

}- Note: As you can see, we’ve specified a specific namespace, because this attribute will eventually exist; it just doesn’t yet, so we define it ourselves in our project.

Now, we need to do the actual interception, specify the code to be replaced. To do this, we use the attribute, which includes the file (the full path), the line, and the character position of the first letter of the method to replace:

public static class Interceptores

{

[InterceptsLocation(@"C:\Repos\csharp12\Interceptors\Program.cs", line: 3, character: 25)]

public static int Interceptor1(this Operacion obj, int a, int b)

{

Console.WriteLine("esto es el primer interceptor");

return a * b;

}

[InterceptsLocation(@"C:\Repos\csharp12\Interceptors\Program.cs", line: 4, character: 25)]

public static int Interceptor2(this Operacion obj, int a, int b)

{

Console.WriteLine("esto es el segundo interceptor");

return a - b;

}

}Notice that this is a static class, and the static method is what will replace the code we use. It also receives a “this” parameter of the type being replaced.

For this example, we’ll replace the use of this method:

public class Operacion

{

public int Sumar(int a, int b)

{

return a + b;

}

}And finally, here is its usage:

Console.WriteLine("Hello, World!");

Operacion operacion = new Operacion();

var result1 = operacion.Sumar(3, 5);

var result2 = operacion.Sumar(10, 5);

Console.WriteLine($"resultado1 {result1}");

Console.WriteLine($"resultado2 {result2}");Once you compile, you can see in the IL code that the calls go to the methods you created:

There are several things about this that don’t quite sit right with me:

The first is the matter of the path, it currently has to be absolute, meaning you need a fixed location for the project. If someone clones your code, it has to be on the same path, which doesn’t make much sense.

Then, the usual concerns such as including malicious code, overriding features, and so on, but nothing serious since it only works at compile time.

By the way, interceptors can only overwrite code in your project, not NuGet packages. Which, in my opinion, would be ideal. And honestly, I don’t see much use for this feature.

7 - Dependency injection with keys

This new version of C# gives us access to what are called keyed services within dependency injection.

And you might ask, what is a keyed service? It’s simple: when we inject the same interface multiple times using dependency injection, what happens under the hood is that we get a list. For example, given the following code, it will inject a list of IEmailProvider:

builder.Services.AddScoped<IEmailProvider, GmailProvider>();

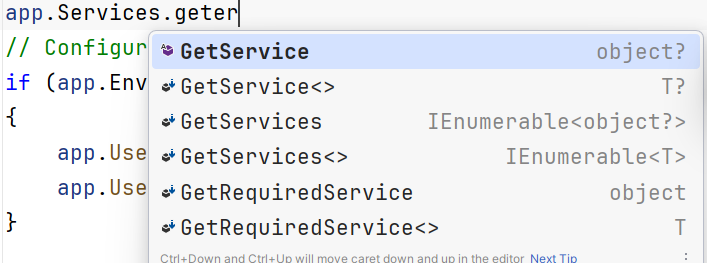

builder.Services.AddScoped<IEmailProvider, HotmailProvider>();By default, when you inject it, you get the last one registered, but if you fetch it manually, you can choose either the first with GetService, or the list.

Now, we have the ability to use AddKeyedService, meaning we can specify a key or identifier for our service:

builder.Services.AddKeyedScoped<IEmailProvider, GmailProvider>("gmail");

builder.Services.AddKeyedScoped<IEmailProvider, HotmailProvider>("hotmail");And then, when fetching, we specify which identifier we want:

IEmailProvider emailProvider = app.Services.GetKeyedService<IEmailProvider>("gmail");

Of course, if we’re in a service, we can inject the one we want to read:

public class SendEmail

{

private readonly IEmailProvider _emailProvider;

public SendEmail([FromKeyedServices("gmail")]IEmailProvider emailProvider)

{

_emailProvider = emailProvider;

}

}

And this is very, very useful, because previously you’d inject the list and search for the one you want, as seen in this code from my distribt library.

But now you might ask: okay, but what real-world use is this? A very simple example is the following: Imagine the code below:

public class SendEmail

{

private readonly IEmailProvider _emailProvider;

public SendEmail(IEmailProvider emailProvider)

{

_emailProvider = emailProvider;

}

public async Task<bool> Execute(string subject, string body, string to)

{

//validations, etc

await _emailProvider.SendEmail(subject, body, to);

return true;

}

}You have a class called “SendEmail” that sends emails using your provider of choice, say Gmail. But for some reason you want to migrate to Hotmail.

Before keyed services, you would have a few ways to tackle this: one way would be to create an IHotmail interface inheriting from IEmailProvider and inject that; another way would be to create a new IHotmailProvider interface that doesn’t inherit and inject that, etc. With keyed services, you can inject both services with the correct interface, simply stating which you want, making migration much easier and without “polluting” the rest of the code.

public class SendEmail

{

private readonly IEmailProvider _originalEmailProvider;

private readonly IEmailProvider _newEmailProvider;

public SendEmail([FromKeyedServices("gmail")]IEmailProvider originalEmailProvider,

[FromKeyedServices("hotmail")]IEmailProvider newEmailProvider)

{

_originalEmailProvider = originalEmailProvider;

_newEmailProvider = newEmailProvider;

}

public async Task<bool> Execute(string subject, string body, string to)

{

try

{

//validations, etc

await _newEmailProvider.SendEmail(subject, body, to);

return true;

}

catch (Exception e)

{

//validations, etc

Console.WriteLine($"el nuevo provider no funciona {e.Message}");

await _originalEmailProvider.SendEmail(subject, body, to);

return true;

}

}

}

And that’s it, these are all the new features in the new version of C# 12!

If you enjoyed the post, don’t forget to share it!

Best regards