Today I want to talk about a pretty important topic, in which I'm going to make a brief summary about APIs and their design.

There are several ways to approach this information; in this post, I'll move from the outside in, where I think everything will be quite clear.

1- Input and Output in an API

From my point of view, it’s better to start with the API entry point, which means starting with the part agnostic to the programming language you’ll use to implement the API. This is the only part where your users or consumers will interact, whether sending or receiving data.

There are several important points here.

1.1 - URL Format

It may sound trivial, but you have to maintain certain standards. The biggest problem I see is that nothing really forces a URL to follow a specific pattern. If you work in the .NET ecosystem, you have likely seen how Microsoft has tried to enforce its own style on everyone instead of adapting to established conventions.

What do I mean by this?

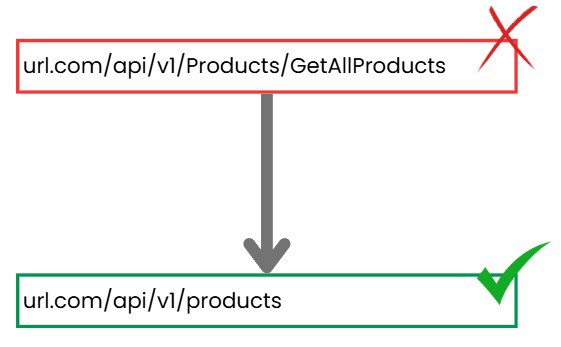

When we have a URL where we want to get a list of products, the standard used is as follows: url.com/api/v1/products

In .NET by default, things work a bit differently.

To implement this functionality, you’ll need a controller and a method inside the controller. You name the controller Products, which turns the url into url.com/api/v1/Products (with an uppercase letter) and then comes the method. If you name it "GetAllProducts", the url becomes url.com/api/v1/Products/GetAllProducts which, while it works, isn’t ideal because we should maintain consistency and not depend on a language or framework.

Key points to consider:

- The full URL must be in lowercase

- It should not include unnecessary elements

Of course, in any language, these configurations can be easily changed, but not everyone does it.

The "GetAllProducts" style is closer to RPC. There are cases where you do RPC over http, but that’s a topic for another post. If you want an introduction, you can check my book Building Distributed Systems.

1.2 - Compound Names

The topic of URLs doesn’t end there. When you have a route that contains a compound name, for example, url.com/api/v1/Products/{id}/UpdatePrice to update the price of a product, you should separate compound names with a dash (not an underscore) like so: url.com/api/v1/products/{id}/update-price

Key points to consider:

- Separate compound names with a dash

Note: {id} represents the unique identifier of the resource.

1.3 - Use the Correct Method

As we all know, when making an HTTP request we have multiple methods we can use; these methods are there to indicate an expected functionality. Although there are more, the most common are these:

GETto read resourcesPOSTto create resourcesPUTto update resourcesDELETEto delete resources

With these, you cover 99.99% of the use cases—and as we can see, it’s very simple. Even so, some people still get it wrong.

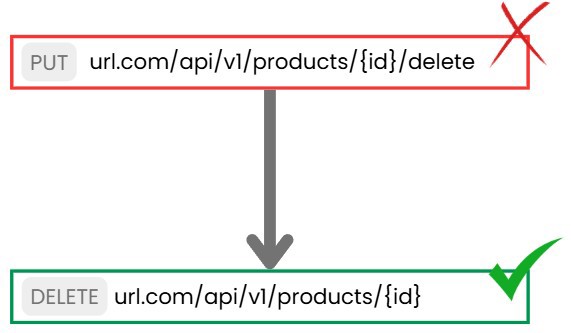

You may have seen cases where POST is used for updating or even deleting resources because, well, you’re not actually deleting the record from the database (if you use soft delete), so a POST or PUT is made. This design is incorrect because from the perspective of the end-user or client, the record is deleted as they can no longer access it.

So, the way to delete a record is as follows: [DELETE] url.com/api/v1/products/{id} As you can see, we’ve applied the previous points in designing this endpoint.

Now comes the case of reading records. When reading a single record, there’s usually no doubt; you pass the identifier via the URL: [GET] url.com/api/v1/products/{id}.

But what happens when we want to get a list of elements, or something even crazier, when we have a search?

In these cases, two options are commonly seen, although they’re not always used correctly.

The first option is to send a POST or PUT even when we’re not creating or updating anything. This is done because we’ll specify all the search elements in the message body.

This option is not wrong if you are using an RPC approach for your API.

On the other hand, if you are using RESTful (which is the most common for any API coming from the front end), these calls should use the GET method, where the parameters are passed as part of the URL.

Even if you’re selecting multiple items, just send them in the URL separated by commas, as seen in the following example:

[GET] url.com/api/v1/products?ids=product1,product2,product3,product4

Key points to consider:

- Use the correct method when interacting with system resources.

1.4 - One Action per Resource

Each API resource should be designed to perform a single action in the system.

For example, if we have an endpoint called [POST] url.com/api/v1/products/update-price we will use it only to update the price of a product.

This endpoint should not update other values like the name or images.

The same applies to an order service if we remove a product [DELETE] url.com/api/v1/orders/remove-item. In this case, if we are in a microservices or distributed system, we must perform two actions. The first is to remove the product from the order. The second is to update the stock, because the product we no longer have in this order should become available. The stock update should not be done from the order service, but by generating an event, which will be listened to by the corresponding service. Read more about event sourcing.

Key points to consider:

- Atomicity of resource functionality

1.5 - GraphQL and RPC

If you use GraphQL or even RPC you will always work with POST and with stricter standards, which is why I haven’t elaborated on them here.

Still, I have posts where I talk about both

1.6 - Other Key Elements

There are other elements to consider in API design, but I don’t consider them part of the basic design since they will change depending on the use case, so I won’t go into them here—besides, this post would then be book-sized.

These elements are the following:

1.7 - Response Status Codes

The most important thing is to use status codes correctly. I’m sure many of you have seen a wrong API response, but then you read the body and it turns out there was an error. This is a big mistake. You have to use the right status codes. We can separate them into different categories:

- 100-199 -> Informational codes

- 200-299 -> Success codes

- 300-399 -> Redirection codes

- 400-499 -> Client error codes

- 500-599 -> Server error codes

If you correctly indicate the HTTP status code, consumers will know whether their HTTP request worked as expected.

Many applications have monitoring, observability, and alert systems automatically, so using the correct code is crucial.

Key points to consider:

- Use the HTTP status code in the response

1.8 - API Response Object

When responding, there are two strategies I like, and we can distinguish them depending on whether we are programming an API or an API + SDK.

From my perspective, when we have an API and are returning values, we should return an object, regardless of whether the call failed or succeeded.

If it fails, we should use the ProblemDetails standard, including error information so that the API consumer can read and understand the issue. This standard is being adopted by the vast majority of companies today.

If the call works, we should respond with the resulting object. Be careful: when returning a response—even if the response is a list—don't just return that list, wrap it in an object so you can extend the endpoint later if necessary.

What is intolerable is responding with null, or a string with the error message and nothing more when something goes wrong. That is not a good practice.

1.8.1 - The SDK Case

When developing an SDK, what we’re doing is building a small package or library that abstracts the calls to the API. In this case, clients don’t interact directly with the API but through our SDK.

In these situations, we slightly change the naming of actions, since clients will work with objects in code instead of HTTP resources directly. Here, we will add the suffixes Request and Response to all objects. For example, if we are querying a particular product, the call will be GetProductRequest, which accepts an ID. Under the hood, it calls [GET]url.com/api/v1/Products/{id}.

In turn, the response will be GetProductResponse and will contain an object, which will have already validated internally whether the API response has any errors or not, so users can access it without any problem.

Key points to consider:

- Return ProblemDetails for errors

- Return an object for successful cases.

1.9 - Open API

Open API is a specification on how we should write REST APIs. With this specification, what we’re doing is documenting, in a standard file, the entry point to the API, so it's crucial to have it done right.

Here, we can specify all the rules we want, and it will serve as a reference for all consumers.

There are also tools that convert the file into code, so integration in any language is minimal.

Finally, the vast majority of programming languages have tools to convert code to the OpenAPI specification automatically with hardly any configuration needed.

2 - Internal API Design

The internal design of an API is very subjective. In this same blog, we've seen lots of completely valid solutions, and some might make more sense than others. In some languages, certain architectures are favored over others.

In fact, on this channel, we've looked at several architectures.

2.1 - Keep it Simple, Stupid Please

You may have heard the acronym KISS which means Keep It Simple Stupid, which in programming means doing things in a simple and "for dummies" way. I like to change that acronym a bit and say KISP, since all I ask is that you keep it simple and don’t over-engineer, please.

So that's it: the fewer inner layers, the better. I’m not saying you should call the database from the controller, but in my opinion, very few applications deserve anything more complex than the core-driven architecture.

Of course, this includes using libraries that make no sense or add no value. For example, the one that is always criticized in .NET is mediatr (and it gets criticized again here) that is added to many projects, but ask yourself: Do I need the mediator pattern in this project? Maybe yes, but if you don’t need it, don’t add the library just because every project does it.

In other cases, do I need the performance gain Dapper gives over Entity Framework when the whole company uses EF… Or the opposite: do I need EF and its entire ecosystem when all I do is call stored procedures in the database?

Comparison between dapper and entity framework here.

Every package, library, and practice has a reason to exist and we must understand those reasons to choose the best options. Choosing only what we know, and not being open to new solutions (or letting go of certain libraries), is not a good long-term strategy.

2.2 - Breaking Changes

A breaking change is when a library, system, or API changes and stops working as it used to, requiring each consumer to change and update.

For me, this is almost always unjustifiable. Having to make a breaking change means one of two things:

- The process is completely different

- It was originally designed incorrectly

Both are problems: the first is more product-focused, the second is more about us as developers.

The ideal is to avoid breaking changes. Sometimes it's completely inevitable, but that's rarely the case when something is well-designed from the start.

Anyone who has dealt with breaking changes knows how annoying—if not worse—it is to have to change code because someone decided a property would stop existing on an endpoint from one day to the next.

That said, depending on the industry you work in and the contracts your company has with clients, making a breaking change can be legally impossible.

2.3 - API First Vs Front End Driven development

The last point I want to mention in this post is how we design our APIs.

Without going into too much detail—since you can find more info in my book building distributed systems—to sum up, we can create APIs in two ways.

The first is API First, which means we create the endpoints and decisions for the API without worrying about the consumers, thinking only about the domain actions on that API. Then, the consumers must adapt to it. This implementation is very popular in mature systems where many systems interact, as this makes the APIs or systems independent from each other.

The other case is FDD or front end driven development, which is when we develop APIs to meet the needs of the front end or API clients. This way, complete development of features is usually faster, but you get some coupling between systems. This approach is very useful as a first step, and I've seen it often—for example, if we are migrating from a monolithic system to microservices, doing FDD is the easiest, as we extract the code as quickly as possible.